The Top 10 Works of Ancient Literature

Suggested by SMSEver since humans mastered the art of recording words in Bronze Age Mesopotamia we have been concocting stories to entertain and inform. This list looks at the very origins of writing, highlighting the top 10 works of ancient literature, with masterpieces from as far back as Sumerian times. Let’s delve into antiquity to see just what the ancients can teach us.

10. Metamorphoses – Ovid

What did the Romans ever do for us? Well, quite a lot actually. Along with pioneering central heating, flush toilets and the structural arch, this mighty civilization also gave us some of the finest works of literature ever written. Ovid’s Metamorphoses, 15 books dramatizing the creation of the earth, the history of Greek mythology and the ascent of Julius Caesar, is one of the most magnificent poems ever put to paper. Published in AD 8, the rich symbolism, astounding use of metaphor and vibrant characterization of Ovid’s crowning work has inspired generations of writers, from William Shakespeare to Ted Hughes. Yet despite literary success, or perhaps because of it, Ovid found himself on the wrong side of the Roman authorities, and was banished from Rome shortly after the Metamorphoses was completed, living out his remaining years in exile on the shores of the Black Sea.

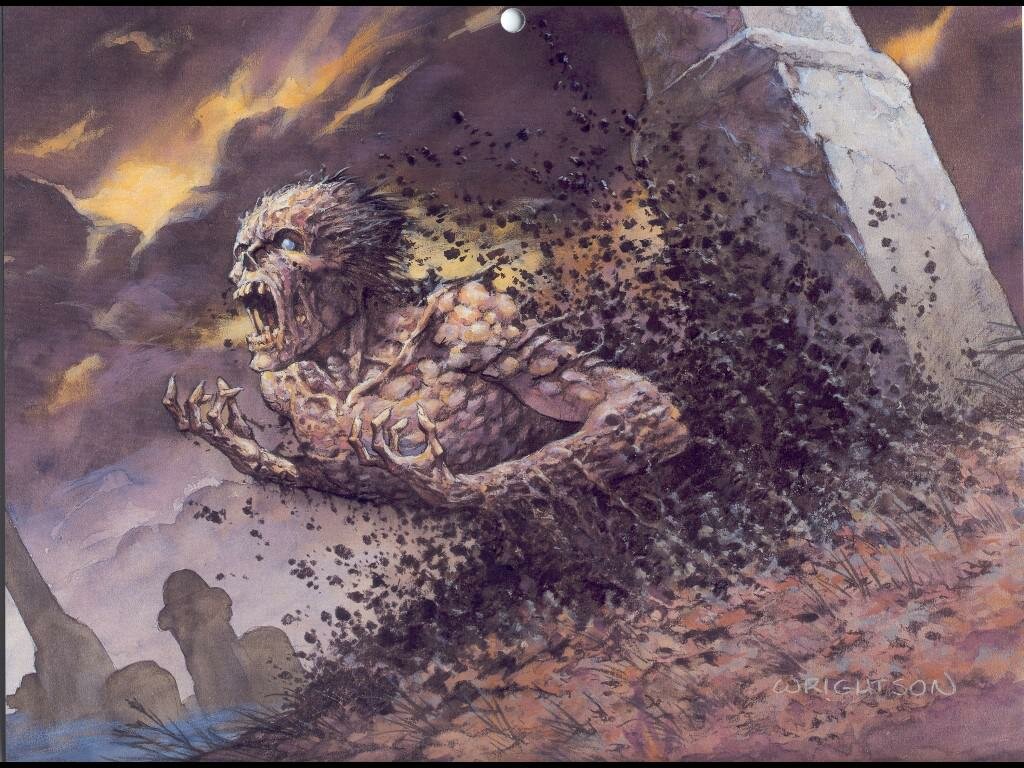

9. The Epic of Gilgamesh

One of the oldest tales still in existence, this Mesopotamian legend can be traced all the way back to the Eighteenth Century BC, when it is thought that Akkadian authors compiled a diverse collection of ancient Sumerian poems and turned them into one coherent narrative. The version most widely read today, however, comes from the personal library of Ashurbanipal, the last king of the Neo-Assyrians, whose vast estate was unearthed in the mid-nineteenth century by British archaeologist Austen Henry Layard. Like many great tales from history, this one follows the adventures of a King, the eponymous Gilgamesh, as he embarks on a series of epic quests and dangerous adventures. Accompanied by his loyal sidekick Enkidu, raised in the wild and apparently covered head to toe in hair, Gilgamesh manages to slay a giant, spurn the advances of a Goddess and slaughter a sacred bull, all in the space of 12 modestly sized stone tablets. Gilgamesh’s search for immortality, however, proves futile, and before the end of the tale he will suffer the tragic loss of his hairy best friend.

8. Odyssey – Homer

The second oldest existing work in the history of Western literature, the Odyssey dates all the way back to the 8th century BC, when it appears Greek bard Homer decided to write a follow up to his first epic saga, The Iliad. Contrary to the theory that sequels never better their originals, the Odyssey is thought by many to be a more dramatic and coherent piece of literature, jettisoning the broad strokes used in The Iliad for a psychologically compelling focus on one single individual, the warrior Odysseus. The book documents this heroic protagonist as he voyages from Troy to his home town of Ithaca, a journey that takes him over a decade. Considering that the distance between the two cities has been estimated at around 500 miles, walkable in less than two weeks, it appears that Odysseus just didn’t want to return home all that quickly. When he eventually makes it back to Ithaca at the end of the story, after pitting his wits against cannibals, sea monsters and a giant cyclops, he is recognized only by his faithful dog Argos, who promptly dies of excitement. With such a warm homecoming on offer it is no wonder he took his time returning from the war.

7. The Aeneid – Virgil

Written between 29 and 19 BC, this was Virgil’s, and Rome’s, attempt to produce a work of such mythic and poetic intensity that it could compete with the ancient Greek epics penned by the legendary Homer. Virgil even took the same incidents and characters referred to in Homer’s Illiad, reworking the story to focus on the Trojan warrior Aeneas, turning one of Homer’s minor characters into the hero of the book. In Virgil’s masterpiece Aeneas travels around the Mediterranean, battling with gods and warring nations, before arriving in the Italian province of Latium to found the city that would later become Rome. One of the book’s most historic passages is our primary source for the events surrounding the siege of Troy, in which Greek soldiers make their way into the city by hiding inside a wooden horse, forever immortalized with Virgil’s succinct phrase “beware of Greeks bearing gifts”.

6. Art of War – Sun Tzu

Loved by personal improvement aficionados the world over, Chinese writer Sun Tzu’s Art of War has a history that belies its current day status as a sort of self-help manual for those seeking to gain an advantage at work. Thought to have first been written on bamboo scrolls and dating back to around 512 BC, a tempestuous period in China’s history, Sun Tzu’s treatise on all things military originally included chapters devoted to the terrain of the battlefield, how to successfully utilize spies as well as guides showing how to employ traditional Chinese weapons. The manual has inspired many commanders down the years, with military leaders such as Mao Zedong, Napoleon and General Douglas MacArthur all testifying to the book’s invaluable influence on their careers, and is today a must read for anyone interested in the history, and indeed future, of warfare.

5. Histories – Herodotus

As philosopher George Santayana once said, “Those who forget history are bound to repeat it.” So one wonders just what the Ancient Greeks did before Herodotus came along. The Halicarnassus scribe pretty much established the genre of history overnight with the publication of his 440 BC blockbuster The Histories, charting the rise of the Persian Empire and the establishment of Greek city states such as Athens. The collection of nine distinct volumes is arguably the most definitive contemporary account of the classical world in existence and startlingly comprehensive in its scope, tackling subjects from the geography of Egypt’s rivers to the spice trade of Arabia, knowledge it is thought Herodotus picked up on his extensive travels. The book, however, is far from a study in rigorous objectivity, with Herodotus firmly planting his flag on the side of the Athenians when discussing the Greco-Persian Wars of the 5th century BC.

4. The Egyptian Book of the Dead

The most famous funerary text of all time, the Egyptian Book of the Dead comprises a number of supposedly magical spells intended to guide the newly dead through the dark underworld and into the realm of the immortal gods. Rather than a single standardized text authored by one recognizable hand, each edition of the Book of the Dead was different, every copy hand-transcribed to order, usually for rich and powerful clients in anticipation of their own death. Copies discovered and on display today vary widely; some boast exquisite calligraphy and illustration, while others are plainly copied onto second-hand papyrus. The original Egyptian title of the book, when translated from Hieroglyphics, reads something like “rw nw prt m hrw”, a mouthful at the best of times.

3. Fables – Aesop

While many works of classical literature can prove daunting to new readers, utilizing dense language and weighing in at many hundreds of pages, the refreshingly easy to read volume known as Aesop’s Fables is something of an exception. This allegorical bestiary of short and simple tales delivering honest and homespun truths has endured for millennia, and is today read around the world by an audience of primarily younger readers. Modern scholars contest whether Aesop wrote the majority of the fables, and even whether he actually existed at all. Yet whatever the truth, these compelling fables remain well known today, with stories such as the Hare and the Tortoise, The Goose that Laid the Golden Eggs and even The Boy Who Cried Wolf dating back to at least the 7th century BC, when Aesop was thought to have penned the collection.

2. Panchatantra – Vishnu Sharma

In the modern world Animal stories such as the Lion King or Finding Nemo have proven to be enduringly popular with people of all ages, and the same was also true in the ancient world. The Panchatantra, said to have been written as far back as the Third Century B.C. by Sanskrit scholar Vishnu Sharma, is a collection of dozens of inter-linked stories in which a host of animals, from owls to jackals, lions to monkeys, play out fables with a strong moral or practical message. Reading the Panchatantra has been compared by modern fans to opening a set of Russian Dolls, each story revealing another hidden inside. One of the most well known of these nested narratives is that of the Brahmin and the Mongoose, in which a Brahman leaves his child in the care of a friendly but occasionally ill-tempered mongoose. On returning the Brahman notices that the mongoose’s mouth is covered in blood, and kills the creature, believing in his haste that it has killed his son. Only later, uncovering his child sound asleep, does he realize that the mongoose bravely defended the boy from a deadly snake, and that he has acted in grave error. The story is one of the most famous of all cautionary tales warning against prejudice and hasty action.

1. Ecclesiastes

Perhaps most well known as twelve chapters of the Old Testament, and famed for coining philosophical maxims such as “There’s nothing new under the sun”, Ecclesiastes is one of the most influential of all ancient texts. Thought for many years to be the work of King Solomon, modern scholars dismiss this premise, the attribute this poignant reflection upon the fleeting nature of life to an unknown Persian King who lived at some point during the 3rd century BC. The over-arching message of this highly poetic work is to assert that all of mankind’s accomplishments are vain and transitory, that the fate of the pauper and the king are one and the same: death. Surprisingly, and in opposition to all other passages in the Bible, Ecclesiastes even casts doubt on the existence of any kind of afterlife. This is a tract that shows just how progressive and philosophical the ancients could really be.