Top 10 Myths about the Hatfields and McCoys

Suggested by SMSThe Hatfields and McCoys are legendary families in American folklore. The Civil War-era families lived in a valley divided by the Tug River that separated West Virginia from Kentucky. It’s been 120 years since the feud “ended,” and in that time, the legend of the conflict spread and become embellished to the point that distinguishing fact from fiction becomes incredibly difficult. Partly, the difficulty has to do with the time period. Records were not kept as accurate in the late 1800s, and the media was characterized by “yellow journalism,” which encouraged exaggeration or flat-out fabrication if it meant selling more newspapers. As can be expected, the truth of these two families pales in comparison to the myth. The legend, though, may have done more harm than good, as it ushered in the stereotype of the lazy, violent hillbilly, which industrialists used to justify their acquisition of the Appalachian lands for timber, leaving a wake of poverty and disease. To help establish the truth, here are 10 myths about the famous families.

10. It All Started With a Hog

The popular legend starts the feud with a disagreement over a hog. It’s commonly thought that this event set off the bitter hatred between Randall McCoy and Anderson Hatfield. As the story goes, McCoy claimed that a hog on Hatfield’s property belonged to him, while Hatfield maintained that the hog rightfully belonged to the Hatfields since it was on Hatfield property. Although this event did happen, it’s not accurate to say it started the feud.

The conflict occurred in 1878. Randall argued that the markings on the hog’s ears were those of the McCoys, not the Hatfields. Eventually, the matter was taken to court, and the Hatfields won when a relative of both families testified on behalf of the Hatfields. (Interestingly, a Hatfield was the judge presiding over the matter.)

Randall McCoy detested Anderson Hatfield before that incident, though. Back in the Civil War, Anderson Hatfield, along with a McCoy, were responsible for shooting and killing a Union general whom Randall McCoy admired. Randall McCoy blamed Hatfield and harbored a grudge that ultimately led to the hog lawsuit.

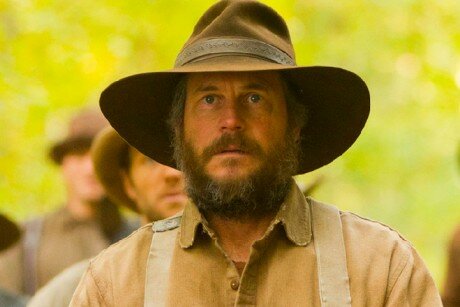

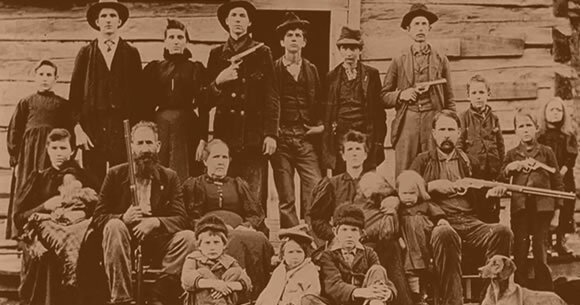

9. They Were Gun-toting Barbarians

The mythology surround the Hatfields and McCoys went a long way toward fueling the image of the gun-toting, lazy hillbilly. A famous picture of the Hatfields, in which even young children are holding guns, furthers the misconception. The truth, though, is that both families were involved in the profitable timber trade. The Hatfields included successful businessmen, teachers, and even a judge.

The Hatfields were more affluent than the McCoys, but the McCoys were not poor, by any means. In fact, they were competitors in the timber industry, which also contributed to their mutual distaste for each other. As a consequence of the feud, it’s said that both families lost much of their wealth, but during the fighting and long before it, the families were successful and reputable members of the community.

8. The Feud Lasted for Generations

Since many generations of Hatfields and McCoys were involved in the feud, it’s easy and common to think the feud itself lasted for generations. In fact, the feud is generally considered to have lasted fewer than 30 years, ending in 1891. Although the first seeds of the conflict began during the Civil War, the first act of violence wasn’t until 1865, when Asa Harmon McCoy was killed.

Trials related to the feud did continue into the early 1900s, but the fighting eased up substantially after the arrest and conviction of eight Hatfields for their raid on Randall McCoy’s house, which killed his daughter. The two families seemed to agree that the convictions, in which seven Hatfields received life imprisonment and one was executed by hanging, would serve as the end of the feud.

7. One Hundred People Died

It’s possible that people think 100 members of the families perished during the feud because they think the feud lasted for 100 years. The truth is that only 12 people were killed, starting with the murder of Asa Harmon McCoy and ending with the execution of Ellison Mounts. In addition, most of the killings happened in a couple of outbursts of violence.

In 1882, Ellison Hatfield, brother to the patriarch Anderson Hatfield, was attacked by three McCoys during a rousing Election Day party. Anderson kidnapped the McCoys and held them captive until he learned whether Ellison survived the attack or not. When Ellison died from his injuries, Hatfield executed the three McCoys in the woods.

The second violent outburst occurred in 1888, when the Hatfields ambushed Randall McCoy’s house, killing his son and daughter and leaving his battered wife for dead. As a consequence of the attack, two of the members who participated in the attack were killed.

Apart from these two events, in which several people were killed, only four members of the family perished during the remainder of the 20+ years of the feud. For sure, 12 deaths is significant in such a short period of time, but it’s nowhere close to popular opinion.

6. One Side Was Union and the Other Side Was Confederate

Many think that the Hatfields of West Virginia fought as Confederate soldiers while the McCoys of Kentucky were on the side of the Union. In fact, both families were staunch Confederates. Anderson Hatfield had formed a militia sympathetic to the Confederacy that actually included both Hatfields and McCoys.

Asa Harmon McCoy, the first killed in the feud, had fought for the Union, but the rest of his family saw his decision as a betrayal. Anderson Hatfield’s uncle, Jim Vance, despised Asa for fighting with the Union and led the charge to murder the young McCoy. They tracked him to a cave and killed him for nothing more than anger at his “betrayal.” After his death, the McCoy clan did not retaliate. Had the McCoys been Union, that would be incomprehensible. Instead, since the McCoys were Confederates, they chose not to retaliate because they figured that Asa had it coming and brought it on himself.

5. Both Sides Had Strict Family Loyalties

Traditionally, the Hatfields and McCoys are imagined as obsessively devoted to their kin. The reality of the situation is that the two families had blended numerous times through marriage and work. Anderson Hatfield employed several McCoys in his timber operation.

During the infamous hog court case, it was Randal McCoy’s nephew, Bill Staton, who testified on behalf of the Hatfields. The jury for that case consisted of an even split of McCoys and Hatfields, and it was a McCoy who broke the tie to swing the case to the Hatfields.

It’s easier to imagine the feud if we create a bitter divide between the two families, but that doesn’t hold up to historical scrutiny. The two families interacted, lived together, worked together, fought in the Civil War together, and not everything led to violent outbursts.

4. Johnse Hatfield Was in Love With Roseanna McCoy

The relationship between Johnse Hatfield, the eldest son of Anderson Hatfield, and Roseanna McCoy is a central part of the legend. Popular myth has them as star-crossed lovers, like Romeo and Juliet. Johnse had said all the right things to Roseanna, and she ended up pregnant. She lived with the Hatfields for awhile before talk of violent conflict between the families prompted her to return to the McCoys on her own. To her surprise, though, Randal disowned her and refused to let her live there. She ultimately moved in with her aunt. Johnse was even kidnapped by the McCoys and Anderson Hatfield led a midnight rescue mission.

Having a tragic love story is so near and dear to the story that it’s hard to dispel, but by all accounts, Johnse was a typical womanizer, and Roseanna was possibly promiscuous. The idea of the two purely loving children may be more accurately described as a lustful passion between members of feuding clans that resulted in a pregnancy. In fact, a few months after Roseanna became pregnant, Johnse married another McCoy named Nancy.

3. The Families Were Entirely Separated by the Tug River

When we think of feuds, we think of opposing factions, and it’s convenient that they occupied two different states divided by the Tug River. It’s easy to think of the McCoys entrenched in Kentucky with the Hatfields fortifying the West Virginia border. Feuds are easier to understand if the lines are clearly drawn and the sides defined.

The truth is much less black and white. The two families worked together and shared relatives. At the time of the feud, the two families were blended together enough that they could routinely interact about town. It wasn’t until the feud ended that the picture looks more like we expect. The Hatfields moved farther into West Virginia, and the McCoys retreated farther north in Kentucky.

Their proximity and intermingling actually helps explain the feud better. If they were separated by the river, they could simply ignore each other as much as possible. Since there was overlap, though, any discontent could easily escalate and lead to the kind of violence that history can confirm.

2. Randal McCoy Was the Undisputed Leader of the McCoys

Most people willingly assign Randal McCoy the esteemed status as leader of the McCoys to counter Anderson Hatfield’s strong leadership of the Hatfields. It’s true that Randal and Anderson were business competitors and didn’t like each other. It’s also true that Randal should have been the logical choice to lead the McCoy clan. However, his actual influence is questionable.

Anderson Hatfield was indisputably the leader of his family. He called the shots. He also seemed to dictate the feud, with Randal being reactionary. History doesn’t demonstrate the same power for Randal. In fact, a relative of Randal’s named Perry Cline seemed to do more to feud with Anderson Hatfield than Randal did. Cline was a lawyer who had a bitter land dispute with Anderson. The land was a profitable parcel for the timber industry, and when Cline argued in court that he rightfully purchased the land, Hatfield was able to counter that the purchase was fraudulent. Hatfield won, took the land, and it became part of his timber wealth.

Cline played a bigger role in getting local and state governments involved in the families’ disputes. He may not have been the frontman for the family, but he may have had more influence than Randal, who was known as more of a complainer and gossip than a patriarch.

1. The Families Handled Their Disputes With Violence

This misconception is connected to several other myths in this list. It fits the conception that two families, bitter divided across a geographic line, staunchly devoted to family, flashing guns, and killing without a second thought. The feud has more romance if the two families opted for backwoods justice, and, indeed, that did happen. Anderson Hatfield’s execution of three McCoys in the woods after Ellison Hatfield was attacked and killed is a perfect example.

However, just as often, the families would turn to the law. They filed criminal charges and lawsuits. They sought warrants. They involved the courts up to the United States Supreme Court. They involved the governor of Kentucky. When they could have used violence to solve disputes, and when they would have, according to legend, they more likely went to the courts to settle things.

The families were too prominent in the community, too wealthy, and too politically connected (especially the Hatfields) to risk becoming outlaws to the extent that legend would have them. Their feud was bitter, and they fired their guns when necessary, but they also demonstrated sound judgment in using the legal system to resolve their differences.

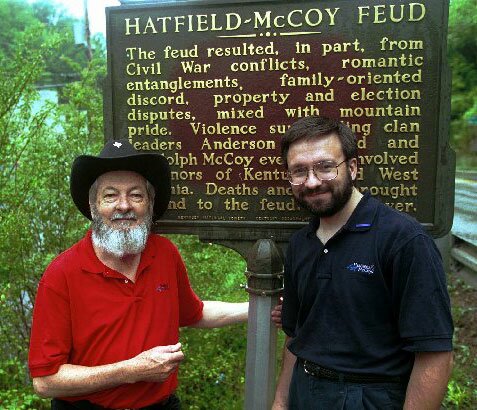

Are there any Hatfields and Mccoys alive today that can trace their roots back?

Im going to check Ancestry.com to see if I am related in anyway, but I think my family had all moved further west by this time period. I’m pretty sure their are plenty of living decendants on both sides. Good article by the way!

I was married to a Hatfield and he was a great great grandson of one of them

There are no original Hatfields and McCoys alive today. But many have traced their roots back to these two families. They have even got the descendants of the McCoys and Hatfields to meet each other – something like a family fued reunion. I thought that was very interesting.

The last of Anderson & Levicy Hatfield’s children, Willis Hatfield, died in 1978 at the age of 90.

But there are lots of descendants. There is a Hatfield-McCoy Festival every June.

There is a Hatfield-McCoy Festival every June.

Yes, I can.

Anderson “Devil Anse” & Levicy Hatfield >> Robert Hatfield >> Craig Hatfield >> Lula Hatfield >> Mary Elizabeth Hatfield >> My Dad >> Me

I was able to trace my family back to Ephraim Hatfield and his second wife. Anderson Hatfield was born to Ephraim and his first wife. There is a great site dedicated to researching the Hatfield name (not just the feuding Hatfields).

The last time I checked, Ephraim Hatfield is as far back as the family tree has been documented.

Wow, who needs the Hatfields and McCoys, when I can just read knight4444 hatred. Far exceeds the result of a hog trial. Great series. We should all learn from history and not use it as an excuse to repeat it or as a crutch to do worse. God bless America.

Your absolutely wrong, I don’t have any hatred towards anybody why are you trying to start this again?? WHY? if you want to contribute to the authors topic do so! I told the TRUTH and if you studied any REAL FACTUAL HISTORY you’d agree with me. Now enough already!

Sir Knight…I did in fact respond to the topic…i.e.great series, learn from history. I just didnt slant it in terms of modern day politics as you did. Not healthy or productive. Again, great series. I watched it in 6 straight hours and learned a bit more about history.

And Sir believe me I wish I wouldn’t have said anything about politics too lol. I study political history and sociology rather you agree with me or not is totally alright with me, I just don’t suffer hypocrites very well. You have a good day

http://www.history.com/news/2012/05/29/7-things-you-didnt-know-about-the-hatfields-and-mccoys/

Another interesting Article. I love the History channel when its about history.

It seems a little Montechio and Capuletto…